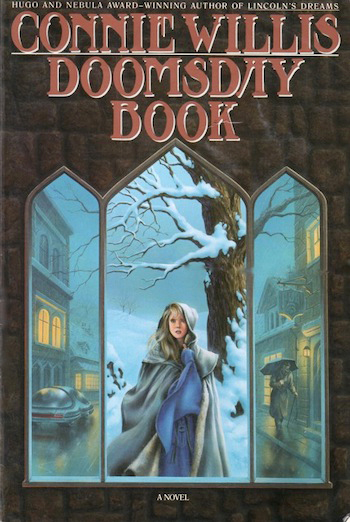

Doomsday Book is a heartbreaking, beautiful, and thoroughly-researched science fiction book about pandemics by Connie Willis. When it was first published almost thirty years ago, it won both the Hugo and the Nebula awards. It’s aged well, and it’s remarkably relevant to today’s real-life pandemic; I’ve found it both cathartic and comforting for me as I shelter in place in my San Francisco home.

I first found this book in my early teens, and the penultimate scenes made me cry and cry. It’s still just as moving, still makes me cry, although my perspective has shifted: I identify less with the excited young student and more with the mentor who fears for her safety, who’s constantly anxious about the systemic gaps around them both. Also, when I first read this book I was an atheist, and since then I’ve come to believe in God. This changed my reading experience, revealing an extraordinary spiritual story I didn’t see before.

I’ve now read many reviews of Doomsday Book. Many contain factual inaccuracies or seem to be missing context. Some people love the spiritual aspect (like me), some don’t notice it (like me when I first read it as an atheist), while others see it and hate it. Given this wide array of reactions, I’d like to engage with the spiritual elements of the story—and also make it obvious that the book stands without them: It won the field’s two biggest awards because it’s an undeniably brilliant piece of science fiction. So I’ll start with a spirituality-free discussion of the science, tech, and futurist visions in Doomsday Book. Then I’ll turn up the spirituality knob slowly, so you can opt out if you prefer not to frame the book that way.

The novel follows two characters: A medieval history student named Kivrin Engle and her mentor, Professor James Dunworthy. It starts in roughly ~2050 A.D., in a British academic time travel lab. Kivrin is headed to the 1300s. Everything is clearly about to go wrong. From page one, Dunworthy is frantic over the time-travel systems Kivrin’s about to use, the inadequate self-interested bureaucracy and buggy technical mechanisms that ought to prepare and protect her. From there, the book is a slow build—the first half feels almost too slow—so it takes a while to grasp the extent of the crisis for both characters: One ends up in a past pandemic, the other in a future one.

The author, Connie Willis, was predicting the 2050s from the vantage of 1992, so the book has some gaps. They’re understandable gaps, but blink-inducing nonetheless: Willis predicted video calls; she did not predict the Internet, mobile phones, or big data. (When Dunworthy gets recruited to do contract tracing, he does it by hand, on paper.) In broad strokes, however, Willis’s observations are spot on. For example, her future history includes a pandemic in ~2020 that forced the world to become more prepared. In other words, Willis, who reportedly spent five years researching and writing this book, predicted that a new pandemic would hit us right about now.

Willis’s future characters in 2050s Britain take for granted the competent, rapid responses of their government and medical authorities—responses shaped by the global pandemic decades earlier. Her imagined future is not without heartbreak, yet she deftly portrays a well-handled crisis, where the global cost is low given the stakes. Her vision includes quietly utopian medical tech: A world that can sequence a virus and deliver a vaccine in weeks; a world where many British young people have never experienced illness of any kind.

Buy the Book

The Angel of the Crows

Given what we’re living through right now, I hope our future plays out this way. I hope we ultimately get a society where sickness has largely passed into myth, yet deadly new epidemics are rapidly identified, isolated, and managed. I want this future so much my heart hurts.

Throughout Doomsday Book, Willis walks a path between darkness and inspiration. It’s full of moving portraits and brilliantly mundane details, some funny and others sobering, like when Dunworthy struggles to recall how he can utilize important contagion-related regulations during the 2050s epidemic. He thinks about how the regulations have been “amended and watered down every few years” since the most recent pandemic—an echo of the institutions our own society weakened in recent years.

The book also offers a critique of organized religion, even as it portrays a spiritual story. This juxtaposition made me curious about Willis’s own beliefs. I didn’t find it easy to discern her religious views from the text, so I tried searching the internet. Within five minutes on Google I found one site that claims Willis is a Lutheran, another a Congregationalist. While some reviews of her books don’t seem to notice any spiritual aspect, others think Willis’s beliefs are “obvious,” while others clearly don’t like it: A previous reviewer says that Willis’s books left her with “teeth gritting questions about theodicy;” in an earlier review, the same person suggests that Willis’s science fiction books be reclassified as “fantasy” due to the religious subtext.

The closest I got to a statement from Willis, herself, is a 1997 interview on an online message board. When asked if religion influences her stories, Willis replied:

I think writers have to tell the truth as they know it. On the other hand, I think every truly religious person is a heretic at heart because you can’t be true to an established agenda. You have to be true to what you think. I think Madeleine L’Engle and C.S. Lewis both have times when they become apologists for religion rather than writers. I want always to be a writer, and if my religion is what has to go, so be it. The story is everything.

Another questioner asked if she has trouble reconciling her religious beliefs with science. Willis responded with characteristic wit:

I have trouble reconciling all my beliefs all the time, particularly with my experience with the world, which constantly surprises, disappoints, and amazes me. I don’t have any problem at all, however, with reconciling religion and science, which seems to me to be the most amazing manifestation of an actual plan and intelligence in the universe (the only one, actually, because people certainly don’t give any indication of it).

I haven’t found more recent interviews wherein Willis discusses religion (if you have, @ me please!). And when I first read and loved Doomsday Book as an atheist, the critique of institutional religion seemed way more obvious than the spirituality underlying her words.

Nothing in Doomsday Book is ever explicitly revealed as an act of God. This means the story’s reality works the same way as our so-called “real life” “consensus reality”: Its technical underpinnings function the same, whether or not one believes in God. I call this “the Paradigm Switch”—multiple frames of reference working simultaneously and seamlessly within a text—and I get excited when books accomplish it, whether they’re fantasy or science fiction. Other stories that pull off the Paradigm Switch include Ada Palmer’s Too Like The Lightning (2016) and Seth Dickinson’s The Monster Baru Cormorant (2018), both excellent, though Doomsday Book’s switch is more subtle. I also can’t resist noting Ted Chiang’s tacit exploration of spiritual themes through time travel, such as The Merchant and the Alchemist’s Gate (originally published 2007 and republished as part of Exhalation, 2019). Sidenote: A book club about science fiction and spirituality that discussed all those stories would be amazing—maybe I’ll launch one! Again, @ me on Twitter if you want in.

Back to Willis’s book: In her critique of organized religion, she imagines future church services that grapple messily with syncretism (syncretism is the attempted reconciliation of different religious practices). Syncretism is modern society’s most important unfinished religious project, so I love it when visionary authors take it on, and it’s extra interesting from a spiritually-inclined author who understands institutional flaws. Willis also gently lampoons how useless sermons can sound when life is at its most challenging. At one church service in the book, Dunworthy is expected to deliver inspiring words; he crumples up the paper with pre-written language and tosses it aside.

More depressingly, in the 1300s plague years, Willis unsparingly shows institutional corruption. Many priests in 1300s England took churches’ money and ran from the plague, leaving no one to care for the dying. Willis depicts how some high-status Churchmen took advantage of dazzled believers’ hospitality and knowingly brought plague to their homes. She also shows how so many priests fled their posts that the Church sent a real-life message around the countryside breaking its own hold on authority, granting laypeople the power to administer the Last Rites. This decree made it possible for more people to make an official confession before they died, which was theoretically important for getting-into-Heaven purposes. A non-Christian might perceive this as a dumb repeal of an already dumb rule, but it’s also possible to see it as a moving attempt to take care of people, from an institution that knows itself to failing against an existential threat; Willis shows both perspectives.

It’s not just the religious characters, though. Throughout the book, some act from self-interest, some from self-righteousness, and sometimes it’s physical, as when a plague sufferer instinctively lashes out and breaks Kivrin’s ribs because she accidentally causes pain in the course of treatment. And in a very modern psychological twist, Kivrin indulges in denial by doubling down on abstract, systems-level numbers. She self-soothes with statistical death rates, as if they’re “quotas” with the power to limit the plague’s devastation. She repeats theoretical percentages like an ineffectual prayer as people die in front of her.

This portrait hit me hard in our era of COVID-19, because I recognize myself in it. I’ve been irritable and difficult and self-righteous, and I self-soothe with theory and statistics, too. I obsessively remind myself of my demographic’s percentage chance of death, my friends’ percentage chance, my parents’ percentage chance—as if those numbers will matter to our realities if any of us contract the virus.

All these deft, dark observations contribute to Doomsday Book and make it worth reading at least once. But what’s brought me back again and again is the exploration of meaning, humanity, and faith in all its forms. Against a backdrop of personal and institutional failures, true faith shines: A doctor’s tireless work on the 2050s flu parallels a lone 1300s priest who never loses his faith, even as he witnesses what he believes to be the end of the world. Meanwhile, the main characters Kivrin and Dunworthy—whose religious affiliations, like Willis’s own, are never explicitly delineated—are both touching examples of people struggling to keep faith and do the right thing in crisis, battered by outside events and internal doubts.

I was raised Unitarian Universalist. This, the most disorganized of organized religions, made it easy to be an atheist teen, which in retrospect I appreciate. It also inculcated a sense that I can find my own truth, which was helpful after I received a sudden belief in God in my early thirties. So I now believe in God, but not quite the Abrahamic notion of God; I might fit Willis’s self-description as a “heretic at heart.” Perhaps that’s why I’m so delighted by the un-dogmatic spiritual story in Doomsday Book, and I’d like to end by discussing the spiritual ideas it stirred up for me. (Note: To be super duper clear, this review concludes with explicit spiritual content written by someone who believes in God. If you keep reading, you’re opting into that.)

My belief in God is experiential, in that it’s based on observation and sensation. Often, when I talk to others, they assume I believe in God because I was raised to do so, or because I heard a persuasive argument, rather than God being a good explanation for a phenomenon I observed. As a result, I take a less theoretical approach to God than many people I talk to (especially nonbelievers with Theories About The Psychology Of Belief). I often think of God and the universe as an aesthetic experience—a self-portrait that provides glimpses of its subject; a story in which we’re the characters, but most of us don’t know the ending. I mention this in the hopes that this could help us study Doomsday Book, as it seems to be a different perspective from that of many other reviewers.

Where might we see, and marvel at, the ways the universe fits together? What elements of this collective art piece might provide clues to the psychology behind it? An example of one concept a human could pick up from observation—a concept that could help us understand theodicy in terrible circumstances, like pandemics—is the concept of parenthood, which Willis tacitly explores.

Pandemics can easily be interpreted in the light of teeth-gritting questions about theodicy. Of many terrible things that can befall us, pandemics are one of the most confusing, the most seemingly senseless. Why, God, would you forsake us so? It’s a question we each asked as children when our parents disappointed us—something all parents must ultimately do, whether in their presence or by their absence; something many children never forgive them for.

In Doomsday Book, Willis offers examples both subtle and strong of why a parent might not be there when needed. She shows indifferent and incompetent parental figures, helpless ones, uselessly overprotective ones. A God with those qualities would not be omniscient and omnipotent, of course—but God’s apparent absence might also be about perspective. Parents often learn the hard way that they cannot protect their offspring from life, that trying to do so not only won’t work, but could ultimately be stifling or backfire.

Christianity explores the parenting lens directly, through the story of Jesus. This is laid out in several Doomsday Book scenes, as when a 2050s priest says during a sermon:

How could God have sent His only Son, His precious child, into such danger? The answer is love. Love.

In this scene, Dunworthy is in the audience thinking about Kivrin, who’s still back in the 1300s. He can’t resist muttering under his breath:

“Or incompetence,” Dunworthy muttered. …And after God let Jesus go, He worried about Him every minute, Dunworthy thought. I wonder if He tried to stop it.

More broadly, an observational perspective might take all the world as data about God, in which case any experience caring for others—any experience relating to anything else, even a virus—could become part of understanding. In the 1300s, as she comes to terms with her darkest hour, Kivrin leaves a message for Dunworthy:

It’s strange… you seemed so far away I would not ever be able to find you again. But I know now that you were here all along, and that nothing, not the Black Death nor seven hundred years, nor death nor things to come nor any other creature could ever separate me from your caring and concern. It was with me every minute.

Free will is an unavoidable theme in stories about theodicy, parenting, and time travel. And as the characters in Doomsday Book go through pandemics and travel through time, they experience shifts in meaning. For instance, while changing position in time—and thereby changing their perspective on time—they know that people who will die in the future are not yet dead. What would it mean to be a God who transcends time, life, and death? How would that relate to free will?

After Doomsday Book I reread another old favorite, Willis’ To Say Nothing of the Dog (1997), a comic romp set in the same time-travel universe (Dunworthy is a character here, too). That too is an excellent novel, far more lighthearted, with similar themes but no pandemics. As I neared the end, one of my housemates put on the U2 song “Mysterious Ways.” The song was still playing when I read page 481, which is set in a cathedral where an organist is playing “God Works in a Mysterious Way His Wonders to Perform.” It made me smile.

Lydia Laurenson is a writer, editor, and digital strategist based in San Francisco. She’s also the founder and editor in chief of The New Modality. She’d love to hear your thoughts about Connie Willis, theodicy, and/or SFF over Twitter @lydialaurenson.

I almost love Doomsday Book. I really do. The scenes in the past are stunningly well written.

But every single time I read it, I get pulled up hard at the notion that massive, seriously massive plot points revolve around the fact that there are no answering machines in this universe. To the point that when I first read it, I assumed that it had been written in the early 70s.

When I found out that it was from 1992? A time when – despite Lydia’s comment that the book failed to predict “mobile phones” I (admittedly an early adopter) had a mobile as my only number?

I’m sorry, but that jars me every time. Which is a pity, because it’s otherwise a remarkable read.

Wonderful article, one of the best book reviews I have read in a while. A depth of analysis and nuanced observation. I have long been interested in how science fiction and fantasy explore religion, too often they do so in a shallow or derogatory manner. I have read Connie Willis before and enjoyed her books, but I will have to go back now and reexamine them in light of this article.

I love Doomsday Book but I always run up hard against the change in tone for Dunworthy in To Say Nothing of the Dog. In DB, he fully realizes that time travel is risky and potentially problematic. In TSNotD, he sends people back in time for little regard for adequate preparation, as if it is some type of game that can be treated thoughtlessly. Argh.

I was intrigued when you said that you were an atheist when younger and now believe in God. It sounds like you were raised without belief in God, but as you say, with a desire for your “truth”, which implies some sort of spiritualism. So there was a tendency toward some kind of belief from early on, right? I’m curious whether you’d say that you were an atheist because you were not taught to believe in God and just never considered it, or because you had considered the possibilities and firmly concluded you didn’t believe.

Your description of your belief in God now doesn’t sound too far from atheism or even incompatible with it. It’s sort of like pantheism, for which I like the description of “sexed-up atheism”. You’re still not believing in a theistic god: an intelligent being who created the universe, is separate from it and who interferes in it. So, it doesn’t sound like there was a great change in your belief in a theistic god, just a change in what you considered to be “God”. Like you don’t believe something exists where it didn’t before; you just see all the same stuff differently, as if seeing it through colored glasses now? Would that sort of accurately describe it?

Truly loved Connie Willis’ brilliant Doomsday Book. And I appreciate this terrific review. For me THE most memorable portrait in the novel was of the heroic, selfless and celibate monk who stayed with and nursed the sick, & then buried the dead plague victims, until the very end, when he himself caught it. To me it is a true portrait of Christ doing the work of love.

The book was utterly ruined by the nonsense plot. No one in the entire universe can overrule a substitute university dean’s arbitrary rule that will result in a student’s death? Food is running out in Oxford even though the trains are still running?

I go on at much greater length here.